Geoff Russ: Rehabilitating George Grant in our age of crisis

Liberal modernity is a tyrant, and Grant remains the champion of a good, beautiful, and better life.

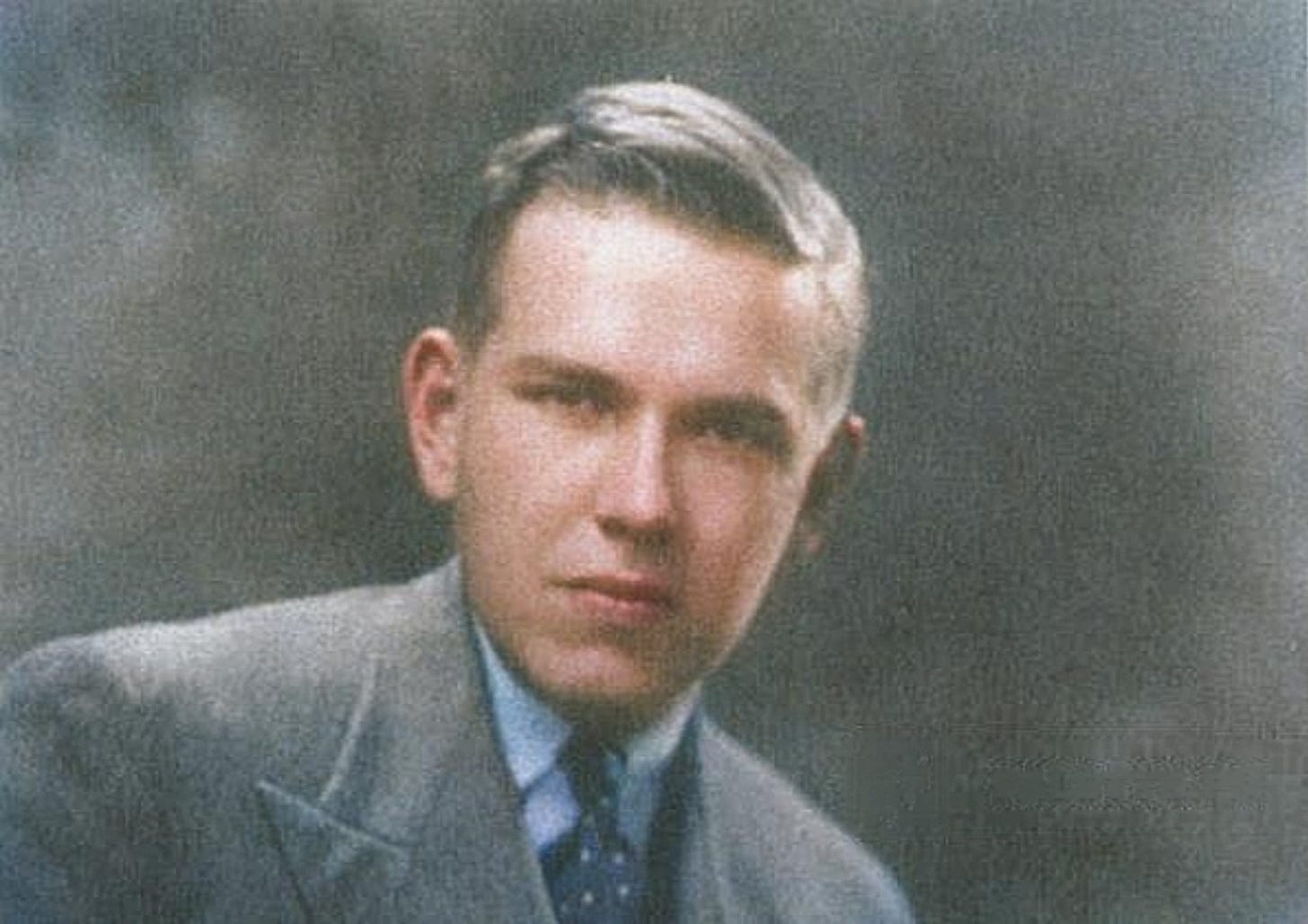

George Grant would have turned 107 today.

Sixty years on from Lament for a Nation’s publication in 1965, the commentary about the man often continues to miss the mark. That is reflected in how the discussion of his legacy centres on Lament, arguably his most flawed book.

Grant’s other works like Technology and Empire, English-Speaking Justice, and his wide collection of essays are left comparatively untouched.

When Grant’s full catalogue is considered, he is less the imperial nostalgic and more the visionary critic of modern liberalism. His warnings about the confluence of technology and rank individualism have proved prescient in our listless decade.

For conservatives and others in Canada and beyond, Grant matters more than ever. As of late, Grant has ironically begun receiving a more genuine and meaningful appraisal in the United States than in his own country.

The power of the classical liberal ethos is waning, and new ideas like postliberalism and national conservatism are on the march.

New Right thinkers like Patrick Deneen of the University of Notre Dame have praised Grant’s critiques of the rootless liberalism that has overtaken the English-speaking world. Others have even favourably compared Canada’s great philosopher to Russell Kirk, the American conservative icon.

In Canada, Without Diminishment is pleased to set the record straight by publishing a special series on Grant, his work, and the pursuit of the good life. For those who refuse to accept the failed status quo, where better to start than with a native son?

Onward.

Part I

George Parkin Grant has not been given his due. He is one of the most unfairly portrayed Canadian thinkers of the past century.

The caricatures of the man, even unintentional ones, continue to make the rounds. For some on the left, Grant is the anti-American Jeremiah they can mine for convenient quotes about the evils of capitalism. On the right, he is often written off as a sort of archaic fogey beset by nostalgia, and forever lamenting the death of British Canada.

Both interpretations miss the mark and the man. Grant’s great project was not rooted in nostalgia or the anti-Americanism of the New Left. It was a serious campaign to name what comprises the good life, and identify the perils of how it is threatened by untrammelled liberalism twinned with the relentlessness of technology.

Today, his insights match the malaise that has stricken the entire Anglosphere.

What George Grant argued

The most well-known image of Grant is of the scruffy, bearded, and portly old academic, leisurely mourning the end of the world he knew. It fails to account for the full life that the man lived.

Grant saw the Blitz firsthand during the Second World War while a student, raised six children with his wife Sheila, and cherished the time spent with them at his picturesque seaside residence in Nova Scotia.

The life that Grant led was one that demonstrated love, fidelity, limits, and duty, all of which are virtues that are lacking in our age. His conservatism drew upon non-liberal ideas, placing him at odds with the tide of right-of-centre politics in Canada at the time.

Grant was also a devoutly Christian man, and his heartfelt Anglican faith deeply informed his life and writing. In this light, it is difficult today to read his work as gloom, and not see it as guidance.

Lament for a Nation is Grant’s most well-known work, and likely always will be. The misunderstood complaint of Lament is not that the United States was an inherently wicked state and Canada a pure nation. Rather, he posited that a smaller, local culture like Canada had been dissolved into the homogeneous, universal order of modern liberal-technological life, led by the U.S. after 1945.

Grant described it as the “pinnacle of political striving” in the modern imagination, and argued that modernity renders all local cultures anachronistic. At the time of Lament’s publication, Grant wrote that Canadians were the neighbours of “the heart of modernity,” and that most of them would come to think that “modernity is good”.

It is an accurate prognosis of Canada’s chronic habit of settling to be a branch-plant country, first subsumed economically, and then culturally and morally assimilated.

Canada’s absorption was the product of a convergence between the language of liberals, multinational corporate power, and the acceptance of modern American progress and technology. In the words of Grant, the U.S. was a “dynamic empire spearheading the age of progress”.

While Grant certainly did not celebrate this, he did not deny that it was a permanent temptation for all modern nations, the Canadians being only one. His arguments are civilisational in nature, not simple nostalgic patriotism for the terminal British Empire of the 1960s.

The hidden tyranny of technology

One of Grant’s core philosophical goals was to expose how machines and our morals can grow from the same root. He argued that it is delusional to assert that “the computer does not impose the ways it should be used”. Both the technological instruments and the standards of justice by which we use them are “bound together, both belonging to the same destiny of modern reason.”

For Grant, it was false to believe that modern tools are neutral entities and that humankind remains capable of fully sovereign choice. It blinds us to how technique scripts the ways we conduct our lives, such as how we live, learn, classify, and govern.

How has your smartphone altered how you interact with the world, and how you classify and think about it?

Classification homogenises, and the systems that oversee it tend toward a bureaucratic, centralised administration that brings technological creep to human life, exactly the drift he warned against in technological society.

Far from being an ideological technophobe, Grant openly marvelled at the modern achievements of technology. However, he warned of the loss of meaning that came with it, a way of life that summons the world before it as an object, and that prizes making over receiving, and the triumph of the will over owing.

Grant proposed that we owe ourselves to the good that cannot be invented, like family, truth, beauty, and God, and accept that freedom is ordered within them. He considered this to be the moral centre of the good life, not progress for the sake of it.

Rights without the good

Grant’s argument against the tide of English-speaking liberalism was not an attack on liberty itself, but on the manner in which it reduces human reason to becoming a servant of will above all.

In English-Speaking Justice, Grant identified Roe v. Wade as a clean example of this. By denying status to the unborn, the U.S. Supreme Court revealed how a vocabulary of rights drives a wedge between life and the triumph of the will.

As Grant’s biographer William Christian wrote, it helped raise the “cup of poison to the lips of liberalism.”

He warned that the same logic would advance further towards the end of life with colourful phrasing, such as “death with dignity” or “providing for those who cannot speak for themselves”. Together with reduced costs and added convenience, euthanasia goes from a tragedy to a bureaucratic method, to the detriment of the value of life.

It drives home the point that once any sense of owing is discarded, an administration arises to fill the void.

Our present unhappiness

Our world today is one where it is hard to have faith that life will get better, or to identify what constitutes the good life.

Across the English-speaking world, there is little prosperity to be found in the soul. From the Financial Times to UnHerd to The Atlantic, we continue to hear of the rising tide of toxic anxiety, especially among young people. The Atlantic, especially, identifies the U.S. itself as a culprit in the exporting of mental-health crises, which Canada imports without any sort of tariffs.

The misery of youth has surged in the United States, Great Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. By contrast, happiness has spiked in many parts of Europe and East Asia.

The telling exception is the French-speaking culture of Quebec, where life satisfaction has fallen “half as much as elsewhere in Canada”. It is not a coincidence that Quebec possesses a relative resilience born of language, history, and separate nationhood. The liberal-technological order grinds away the fastest where it can run with the fewest barriers, exactly as Grant foresaw.

When Grant warned of the “branch-plant” economy of Canada in North America, it referred to culture as much as the nearest General Motors factory. At its root, Canadian liberalism is an offshoot of postwar American progressive ideas of the state and of society, with openness as an end in itself.

It is obvious that Canada is coated in American culture, made only easier by the streamlining of cultural intake, making it especially vulnerable to the export of anxiety as described in The Atlantic.

UnHerd has found similar developments, with a rise in loneliness and people eating alone, while the world’s highest proportion of children in single-parent households now live in the U.S.

Grant would have pointed out that this is the moral bill for the course of action that Canada chose in the 1960s, as institutions like the family, conventional sexuality, and traditional morality came under attack.

What is the way forward and away from the unhappy age?

Contemporary writers and thinkers are starting to converge on Grant’s ideas, even unintentionally.

Without Diminishment’s newest contributing editor Étienne-A. Beauregard has written of a generational turn in politics, with young voters drifting away from progressivism out of a craving for meaning. For conservatives, Beauregard writes that the new task ought to be rebuilding the “cultural, moral, and traditional foundations that make freedom possible.”

In this regard, Grant has nothing to offer a modern Canadian left that treats the social and cultural malaise as a triumph. However, Grant is an untapped well of wisdom and purpose for the right.

Family rapidly feels more and more like a luxury lifestyle, due to fears of the financial costs among young people in an already expensive Canadian society. They want order and a sense of place in a country that is “stripped of landmarks” due to a federally sanctioned mission of national deconstruction and libertine social policies.

Without Diminishment contributor Matt Spoke wrote that the family is the “first institution”, and culture must be lived, not merely legislated or fought about online.

Both pieces entail exactly what Grant termed “owing”, or the goods that cannot be bargained for, and which inform our loves and lives. He insisted that the true, the beautiful, and the good belong together, and that a new, humane politics ought to be measured by those standards, rather than the latest technological advancements.

It is no accident that Patrick Deneen, the American author of Why Liberalism Failed, and perhaps the most influential postliberal theorist of our time, has written in appreciation of George Grant.

In Why Liberalism Failed, Deneen asserts that “liberalism’s success today is most visible in the gathering signs of its failure”. He rightly points to how radical individualism demands ever more statism to guarantee new rights and entitlements, and how a regime’s anthropology shapes its technology. It is a perfect companion to Grant’s writings contained in Technology & Justice.

Grant argued that liberal norms built the political technology that shapes our social technology, and that we decided first to be the kind of people who live by choice without obligation. That decision was buttressed with new devices and authorities that urge us to forget that we ever owed something to anyone or anything at all.

The rise of the American-led liberal-technological order opened Canada up to the ideas that have so thoroughly deconstructed and uprooted a distinct culture and society. By that same token, Canadians can readily access the ideas of thinkers like Deneen and others, giving us inspiration to take a new path, if we choose it.

The value of Grant today

Some of the contemporary takes on George Grant have made the mistake of reducing the man to a single book or mood, leading to unserious characterisations and dismissals from both the left and right. Judging Grant by Lament alone is like judging a house by its door, and ignoring the rest of his large and accessible body of writings that challenge the common assumptions of today.

He was a Christian Platonist who correctly predicted the course of technological liberalism, warned of placing individual will above all else, defended what is owed to inheritance, and championed a Canada that could be more than a satellite.

There is a clarity to Grant’s thinking. He wrote of people who readily trade for modern goods, thereby owing themselves to powers they cannot govern, and how supposedly neutral devices carry their own moral language within them.

A Canada that defines itself by another country’s modernity will import both its goods and its ills. The enduring forms of life, starting with the family, have to be rebuilt, for they are what makes freedom meaningful. Even if the attempt fails, it is better to have tried, for the conditions of the good life must be recovered to bring us out of these terrible times.

Canadians, especially the young, beset by rightful anxiety and hopelessness, have increasingly expressed blacker and blacker thoughts about the future.

George Grant’s legacy is more than a short elegy for the lost world of British Canada, and is a working manual for a more humane Canada. If we live the first institution of family, and orient our politics towards what is true, good, and beautiful, we may yet trade our lament for a recovered hope.

Geoff Russ is the Editor-at-Large of Without Diminishment. He is a contributor to a number of publications, including the National Post, Modern Age, and The Spectator Australia.

Has there ever been a successor to Grant as a philosopher of Canadian Conservatism?