Anthony Koch: The state is the architect of culture, not a spectator

Neutrality is a myth, and states decide what traditions become heritage or contraband, writes Guest Contributor Anthony Koch.

Anthony Koch is the Managing Principal of AK Strategies.

Recently, Sean Speer of The Hub has argued that the state is “a flawed instrument for generating thick cultural norms.” He contends that it can enforce rules and deliver public goods but cannot manufacture belonging, identity, or virtue.

Culture, he says, emerges solely from families, faith traditions, and voluntary institutions, while the state merely stays out of the way.

This is surely a comforting idea, but one that is historically, philosophically, and empirically false.

The modern state has long been the chief engineer of national identity. It is both its manager and creator, and the entire history of nation-building proves this.

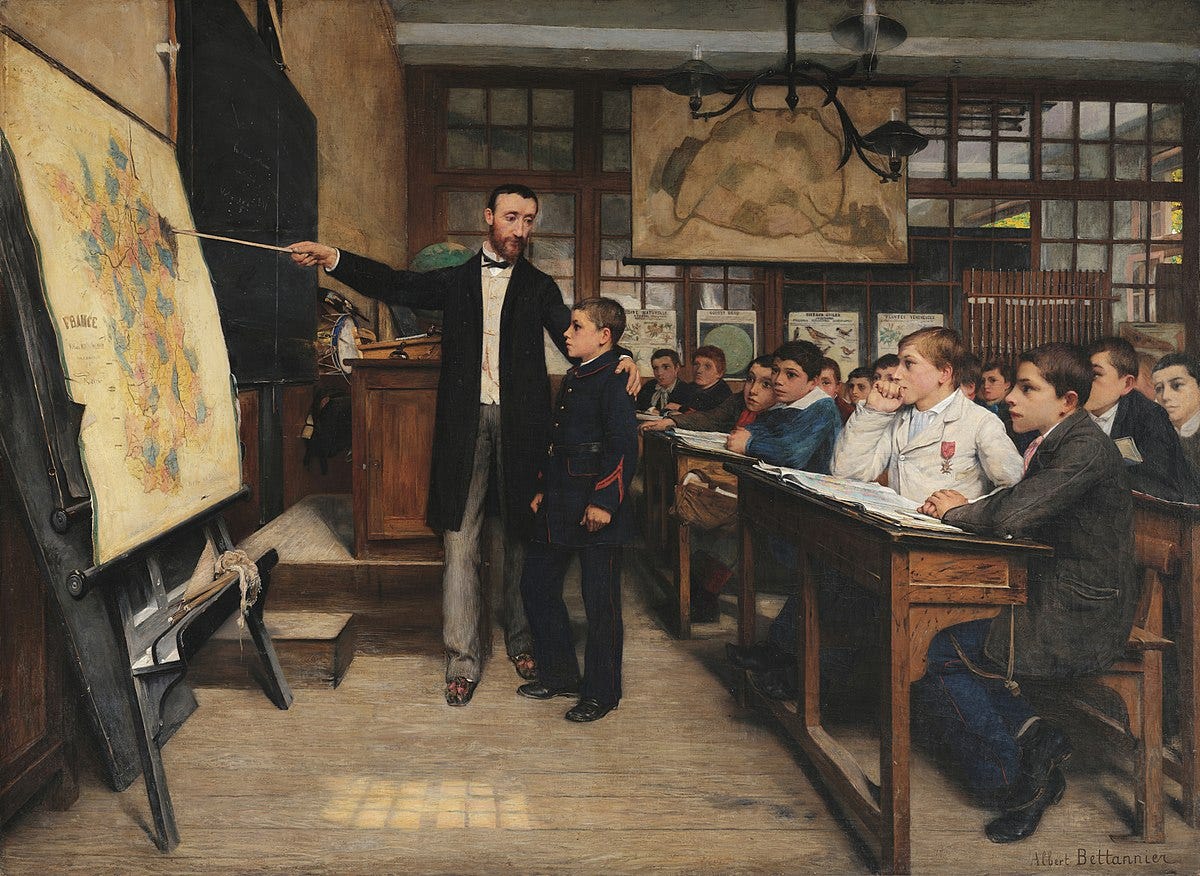

Germany, Italy, France, the United States, Japan, and modern Canada were not spontaneously formed by families and faith traditions. Rather, they were willed into being by political decisions, with maps drawn, schools standardised, languages imposed, songs canonised, heroes selected, histories curated, and civic rituals designed to turn strangers into compatriots.

To deny this is to deny history itself.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote that politics is how a culture saves itself from itself. It is the act of taking impulses, instincts, customs, and contradictions and choosing which shall be elevated, preserved, encouraged, and transmitted to the next generation. Without politics, culture is raw material; politics makes it a civilisation.

That is why the 19th-century European nationalists did not simply hope for nationhood, but actively legislated it into existence.

The unification of Italy was not the inevitable blossoming of regional dialects and parish traditions. It was a deliberate project, accomplished through the political imposition of a national language, a common curriculum, a centralised administration, military conscription, and a mythic lineage back to Rome.

Likewise, Germany was not the spontaneous expression of Swabian villagers or Rhineland merchants.

Prussia strategically forged common institutions, shared enemies, and a common educational canon. Its French nemesis did not stay out of culture either. The Frenchman was created through compulsory schooling, standardised French, often violently imposed on Breton, Occitan, Basque, and Alsatian speakers, and the deliberate elevation of national heroes. The modern French identity, like nearly every national identity, was manufactured by political will.

Speer’s claim that institutions merely reflect a broadly shared culture is precisely backwards. In fact, institutions produce and curate shared culture by selecting between multiple competing visions.

These choices are how they define the nation. Culture is never neutral and always political, because what survives is what is institutionalised.

With all due respect to Speer and his role in the conservative movement, he himself inadvertently concedes the point, because he now observes, with deep concern, how the progressive left has successfully captured our own institutions over the last thirty years. Schools, courts, universities, media, HR departments, policy frameworks, and bureaucratic language all now speak a single ideological, inorganic dialect.

None of it simply trickled in quietly from kindergarten story time and Sunday dinners. It is a triumph of state capture and the institutional levers that come with it.

The progressive movement conquered culture by taking the schools, the credentialling process, the language of law, the codes of bureaucracy, and the rituals of civic life. Through those instruments, they created a new Canadian, one who speaks their language and breathes their moral air, often without realising it.

The proof that the state manufactures culture is that we are now living inside a culture that has been remanufactured.

This is precisely what Speer wants to fight against, but his own argument denies him the tools. To say the state cannot produce identity or virtue abandons the field to those who already understand that it can, and have already done so.

No serious student of history can believe that culture simply emerges, like mist or weather. It is shaped, preserved, or abandoned. It can also be nurtured, logged, paved over, and standardised into extinction. The state, whether Speer wishes to acknowledge it or not, is the single most powerful tool in human history for choosing the story a civilisation tells about itself and what it chooses to forget.

The families and churches that Speer invokes do not exist in a vacuum and stand or fall at the discretion of state instruments. These include legal codes, bureaucratic pressures, regulatory burdens, educational incentives, and cultural priorities, all of which are moulded by the state.

A school curriculum can erase a thousand years of memory in one generation, while a regulatory policy can kill a faith community without once mentioning religion. A tax structure can gut the family before a single sermon is preached in its defence.

The state is not merely a reflection of a culture. It is an arbiter of which traditions become heritage or contraband.

One need not be a statist to see this truth. All that is required is to open a history or sociology textbook, and then walk through a Canadian public school, where the last thirty years of ideological conquest are now taken as sacred truth.

The progressive left understood something that Speer denies, namely that identity can be engineered.

When the young recite your slogans as moral axioms, when public institutions normalise your worldview, when language itself changes to reflect your assumptions, you have not merely joined a debate. You have become the culture.

The question, then, is not whether the state shapes identity; it always has. The question is whose identity it will shape and in which direction.

Speer’s position imagines that neutrality is possible when it is, in fact, impossible. A state either cultivates the soil of a civilisation or allows it to be ploughed under. The soil will not lie fallow and await someone to till it.

The state is never a spectator. It is either the bulwark or the battering ram.

Anthony Koch is the Managing Principal of AK Strategies, a Conservative strategist, and a political commentator. He served as National Campaign Spokesperson for Pierre Poilievre’s Leadership campaign and Director of Communications and Chief Spokesperson for the 2024 BC Conservative election campaign.

Well constructed…great argument and quite convincing

If we created our cultural institutions through the family, faith traditions, and voluntary associations, why can it not be believed that we also created the state as an institution which also embodies our culture? This is fundamentally my trouble with Speer and his more libertarian fusionist view. The state somehow exists outside society, and not something generated by families, faith traditions, and voluntary associations as a way to mediate value disputes along side courts.

Essentially, I disagree that the state can produce identity. The state can foster and support, or oppress and denigrate identities, but it cannot create them whole-cloth. groups which create coherent identities come together and petition the people to use the state to support those identities.

Culture is not down-stream of the state; the state does not create culture. States and governing institution are down-stream of culture; culture creates the state. This is why we as conservatives must articulate a positive cultural image, including a vision of the arts. Once the majority see the beauty of the conservative vision, the state will come to reflect it.