Eric Kaufmann: The crisis of nationalism on the Canadian right

When the left defines the country, the endpoint of individualist conservatism is anti-Canadianism.

Eric Kaufmann is an author and a professor of politics at the University of Buckingham, where he established the Centre for Heterodox Social Science.

Anglo-Canadian conservatism shifted from an older British loyalism to American libertarianism after the 1960s. The Canadian right has gone down the individualist route. In part, this is because Canada’s progressive establishment aggressively polices expressions of cultural conservatism.

The endpoint of individualist conservatism in a left-defined Canada is anti-Canadianism, whether in the form of western separatist movements and alienation, or American annexationism.

Exhibit A: On March 15, Billboard Chris, the Vancouver-area anti-trans activist campaigner, asked his Canadian followers on X whether they would join the United States if everyone in their family was given $100,000. Of the nearly 24,000 who saw the poll and answered it, 86 per cent said yes. The survey is not representative, but national polls find that over 20 per cent of CPC voters would join the U.S., with 27 per cent willing if each Canadian were given $60,000. These levels are several times higher than among voters for left-liberal parties.

In a 2017 English-language survey of 600 people I conducted on Prolific, CPC voters, by a 57–37 margin, said they would sell Canada to the U.S. if everyone got $1 million. Liberal, NDP, and Green voters disagreed by 60–26. This is not normal for conservatives in the West, who tend to be highly patriotic.

In Britain, I ran the same question in 2020. Tory voters opposed selling Britain by 42–38, compared to Labour voters at 52–31. The gap between Brexiteers and Remainers was even smaller. In other words, while ideology inclines right-wing Britons and Canadians toward America, Canadian conservatives are less attached to their national identity than their counterparts in other countries.

The central issue is that Canada was reinvented in the 1960s from British America to left-liberal America. When people disagree about politics and one side is written out of the national story, it is not surprising that the excluded may choose to opt out.

Once upon a time, Canada was defined as a conservative country, and radical liberals were pushed into being the pro-Americans. William Lyon Mackenzie, leader of the 1837 Rebellion of Upper Canada, attacked the country’s Tory loyalism and urged it to join the United States, whose Republican form of government he admired.

Goldwin Smith’s argument for joining the U.S. in the 1870s championed the economic advantages of doing so against the constraints imposed by membership in the British Empire. In both cases, liberal individualism powered pro-American sentiment. That remains true today, even as the country’s identity has rotated from conservative to left-liberal, rendering Canada’s conservatives the new Americophile outsiders.

While the decline of British loyalism, as George Grant lamented, was a major factor in the Americanisation of Canada, shifts on the Canadian left have also been important. Multiculturalism, an idea which originated with the American pluralist movement of the 1910s and 1920s, was officially adopted by Canada in 1971.

The “cultural turn” of the left from class to identity became highly influential among Canada’s Pearson-Trudeau intellectual elite. Political correctness was eagerly lapped up by Canadian intellectuals, forcing criticism of immigration and multiculturalism out of bounds. Though the Reform Party was primarily motivated by American-inspired economic libertarianism, it was most ferociously attacked for questioning multiculturalism and Canada’s comparatively high immigration levels.

Canadian conservatives learned that, to make their case federally, they must stick to the sandbox marked “economics.” In other words, the country’s Overton window only accepts economic individualism, not Anglo cultural conservatism.

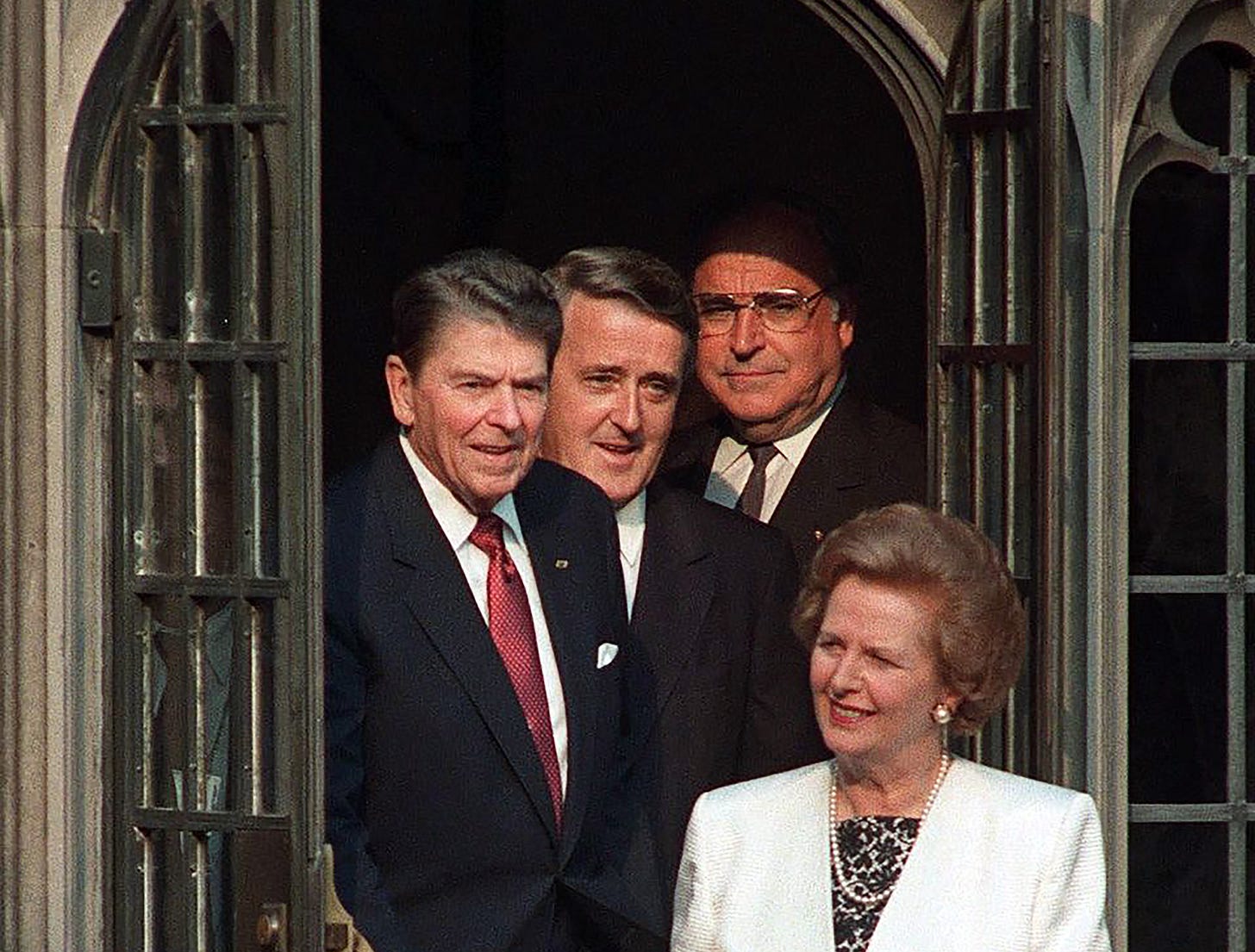

Pierre Poilievre, who has been reluctant to concentrate on immigration and culture war issues such as gender ideology, or the veracity of the residential school genocide narrative, demonstrates the enduring power of these progressive boundaries in the country’s elite political culture. Boxed in by political correctness, he usually sticks to espousing Reaganite economic individualism and anti-government sentiment.

Yet recent developments suggest change may be in the air. Quebec separatism is far from the threat it once was, and Canadian conservatives are no longer focused on bilingualism and French-only language laws. Quebec’s conservatives are more concerned with immigration and Islam than Anglophones, drawing them closer to the cultural mood of conservatives in English Canada.

At the same time, the realignment of conservatism across the West from economic left-right questions to cultural globalist-nationalist ones is breaking apart old coalitions. Cultural issues, including immigration, are becoming more salient for conservative voters.

Where talk of “Founding Peoples” was once associated with Quebec separatists and squishy Liberal compromises with them, it is now attacked by the left as settler-colonialist and exclusionary. Meanwhile, ethnic dynamics are in flux. Many non-British and non-French ethnic groups are more assimilated and secure, and thus less supportive of emphasising difference and multiculturalism than they were in 1971 or 1995.

In combination, this opens up the possibility that a Canadianism based on a common heritage of the British, French, and Indigenous Founding Peoples, in a harsh, beautiful land, could become the basis for a particularist cultural conservatism that Canadians of all ethnic, racial, or religious backgrounds can embrace.

Mark Carney is actually right that, were it not for the remarkable interaction between an unusual set of distinct Founding Peoples, in places such as Annapolis Royal in the 1760s, Canada may well have never come into being.

I would add that questions about collective identity, “what makes us distinct,” cannot be reduced to questions of exclusion and membership, “who belongs,” without committing the fallacy of composition.

An immigrant with a foreign accent who is committed to Canada is as Canadian as someone who sounds like Bob and Doug Mackenzie, but not all accents are Canadian accents.

The Canadian one is still a distinguishing feature of Canadian identity in the world, and the immigrant would doubtless take pride in that accent. So too for the unique combination of British, French, and First Nations ancestry and cultural heritage, which is vicariously the property of all Canadians who identify with the country, including recent immigrants.

While the left will cry “exclusion,” thereby committing the fallacy of composition, the reality is that these features are fully inclusive, so long as ancestry is not used to draw social distinctions. And just as a critical mass of people speaking with a Canadian accent is important for cultivating Canadian distinctiveness, the same holds for preserving a critical mass who reflect the ethnic traditions of Canada.

Over generations, the Anglo-Canadian, French-Canadian, and First Nations melting pots continue to bubble through intermarriage and assimilation, drawing people toward Canadian ethnicity.

If Conservatives can associate themselves with Canada’s founding heritage and landscape, as well as the proud past that Liberals such as Justin Trudeau constantly disrespect, this opens up the possibility that the right can once again, as in Sir John A. Macdonald’s day, own Canadian patriotism.

Ideally, the Liberals would eventually see sense and seek to outflank the Tories on heritage Canadianism, competing to reinforce a consensual set of national symbols and memories.

What the country needs is to detach its identity from ideologies of left or right, thereby developing an authentic Canadianism rooted in the country’s British-French-Indigenous founding traditions and northern landscape.

This, surely, is better for the country than a Canadian right wedded to individualism, or a censorious post-national left that wants Canada to win the prize of the Eldest Daughter of the Church of Woke.

Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at the University of Buckingham. He is the author of The Third Awokening and Whiteshift. He received his BA from The University of Western Ontario, and his Masters and PhD from the London School of Economics. He has also written for the New York Times, The Times of London, The Wall Street Journal, and National Review.

"Over generations, the Anglo-Canadian, French-Canadian, and First Nations melting pots continue to bubble through intermarriage and assimilation, drawing people toward Canadian ethnicity."

That is a very Laurentian view of Canadian history. From the western Canada perspective, we have a long history of a more liberal perception of society, and refusing to bend tk the Laurentian knee.

Consider Riel and the Red River Resistance. Riels demand for rights is clearly in line with a liberal world view.

Or perhaps we should consider that in the period of liberal supremacy between Benette and Mulroney there was the short lived Joe Clark, and the one term Diefenbaker, who brought in the very liberal individualist bill of Rights and represented the relationship between immigrant Canadians and their love of the British institutions which Canada had.

So when I read this article, or the one the other day on the Anglo Canadians related to the flag, I can't help but feel like I'm seeing the same smug Laurentian anti-western core which has animated Prairie populism for the last century, and underpins the modern conservetive party.

How can the Canadian New Right be blind that a new conservstism must find a way to blend the older Anglo-Toryism of the east with the America-Conservsfism of the west into a unique and different sythasis or Fusion than we saw come out of America?

Better, maybe, but I don't see it happening. We continue to slide toward a heavily censored socialist totalitarianism, and I don't think the US is anywhere far enough away, to get from it. Maybe Peru.