Victoria Savage: The Conservatives won over workers, but can they keep them?

Working-class voters can be a powerful part of the Conservative coalition, if they are not taken for granted, writes Guest Contributor Victoria Savage.

Victoria Savage is the creator of the Canadian Nationalist Library.

When talking to young conservatives of the ‘new right’ variety today, one core sentiment consistently emerges. They realise that the fight today is for more than marginal tax cuts; it is a fight for the soul of the country.

There are some who recognise that the existential nature of this fight means that allies can be found from across the political aisle, at least when it comes to economics. The working classes, especially young people, have become a fixture of the new right not just in Canada, but across the West.

For example, in Britain, even before the surge of the Reform Party, the Boris Johnson-led Conservative Party won a majority in 2019 on a platform to ‘Get Brexit Done’. In the process, he managed to break through the ‘Red Wall’, a collection of long-standing Labour constituencies in the north of England populated by predominantly working-class voters.

Similar stories can be found in Eastern and Central Europe. In Poland, the Law and Justice Party has campaigned chiefly on nationalism mixed with ‘New Deal’-style economic policies, fashioning itself as the party of the “regular Pole”. In Hungary, Orbanomics is the eponymously named policy that has kept Viktor Orbán in office since 2010, and which advocates for a strong state in matters of both economics and culture.

We might call this new alliance the “new” right. In Canada, however, there is not necessarily anything new about it.

Like it or not, there exists in Canada a tradition of an older conservatism, or ‘Toryism’ if you will, that predates Reagan, Thatcher and neoliberal economics altogether. It is a belief that only in the blending of society and government, and of culture and economics, can you create a nation that is both good and prosperous.

After all, it was Conservative governments that gave us much of our nationally and provincially owned public infrastructure, such as a national railway and hydro-electric projects across many provinces. They laid the foundations for a national broadcaster and publicly run medical insurance.

R. B. Bennett, the Conservative Prime Minister who led the country through most of the Great Depression, attempted a Canadian version of the ‘New Deal’, albeit too late to salvage his electoral fortunes. He introduced legislation for progressive taxation, maximum working hours, the first unemployment insurance, pension plans, and relief for farmers.

Or what about the Port Hope Conference conservatives? They were a group of young conservatives in Ontario who attempted to revive their faltering party in 1942.

The 800 delegates to the conference advocated a policy plan that called for access to better jobs and better pay, public insurance for unemployment, sickness, old age and accidents, an even playing field for farmers, and the creation of a labour relations board.

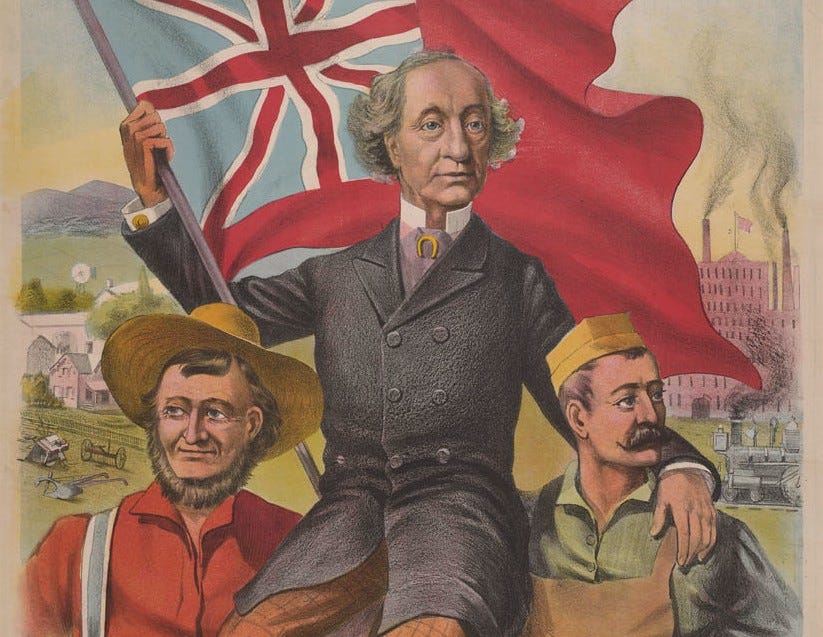

And what about Macdonald?

The Old Chieftain has spent the last few years with his social and cultural views on trial, with little attention paid to his economic programme. His National Policy became the core economic and political policy of the Conservative Party for the first half of its existence.

The National Policy called for high tariffs on imported goods, government intervention in the economy and industry, and subsidies for Canadian products and producers so they could better compete in global markets.

Macdonald also legalised the formation of unions through the Trade Union Act, Canada’s first labour law. Was it done to score political points against his electoral rivals? Sure. But it remains the foundational stone upon which successive pro-worker policies have been built in Canada.

How many conservatives of the neoliberal flavour today, who wish to see his statue returned to their empty plinths, would deride similar policies now as mere ‘socialism’?

Yet this kind of state capacity, infused with a cultural project that is patriotic and rooted in tradition, is what many younger conservatives are clamouring for, and wish the current leadership of the Conservative Party under Pierre Poilievre would lean harder towards. Poilievre could easily rely on these global trends as well as broad political traditions within Canada in order to make a strong case for this renewed, interventionist conservatism.

For Poilievre to adopt not just the vibes but the policies of the new right, he will have to go deeper. He will have to admit that the reason “Canada is broken” is not just owing to a variety of taxes he finds objectionable, and concede that the issues facing young and working-class Canadians are more structural, and more existential.

As long as Poilievre is challenged almost exclusively by different variations of liberals, he may never have to commit fully to this pivot. But it would be remiss of us to imagine that the Conservative Party is the only party seeking renewal, and the only vehicle by which people may express their anger.

An NDP that seeks to regain the trust and support of its once-stalwart working-class supporters, such as one in the hands of someone like Rob Ashton, who is running for leader of that party on a promise to put power back in the hands of workers, could eat away at the gains Poilievre has made among many of these voters.

There is also always the possibility that if moderate, big-tent parties like the Conservatives do not start to take these existential questions and issues seriously, and talk about them in an honest but measured way, then more radical and less restrained movements will fill the space instead.

Those Red Wall voters in Britain who lent Johnson their votes in 2019 have, six years later, abandoned a Conservative Party that was unwilling to part with its commitment to neoliberalism and cultural decline. In Canada, as in Britain, if young, working-class voters continually ask for policies that no mainstream conservative parties are willing to offer, they will turn to more radical options for answers.

The fight for the soul of the country is a worthy one, and conservatives must be willing to commit to the fight on both culture and economics. The future of the Conservative Party, like its past, is interventionist in nature. Will they realise it in time?

Victoria Savage works in cybersecurity, and is a former political staffer. She holds a degree in Political Science and History from the University of Ottawa, and is the creator of the Canadian Nationalist Library.

Great article- am stuck right in the middle- generally not in favor of government intervention however at this stage of the game not sure a conservative effort without intervention would succeed either. I don't know what to think anymore.